Placenames

Placenames

Here are some thoughts on placenames that are found on our maps and how I have approached the task of deciding which names to show, where to place them and what forms to use. Placenames are the labels we apply to the features and divisions of the landscape which we inhabit and visit. Like language, they change over time but there is a thread of continuity in many placenames that connect us back to the previous generations that also gazed at and toiled on the same landscape. It is a matter of courtesy and also of practical benefit to be familiar with the placenames both of where we live and also those regions that we visit for recreation. We give these labels to the landscape for various reasons but primarily concerned with ownership, description/ directions and in connection with farming & fishing etc.

Before we proceed further, please note that I write fairly regularly on specific placenames and associated history on our Facebook page at EastWest Mapping Facebook

Anyone can look these up and scroll back. To receive regular updates, you’ll need a Facebook page and make sure to Like our page to receive one or two news snippets per week.

You can also refer to a related bibliography and list of useful websites at the foot of this article.

Note also that I don’t claim to be an academic of language and placenames but I have a longstanding interest in the countryside and hills and have learnt a lot about the subject by talking to local people in the districts that we have mapped. I’ve always had an eye for landscape & topography and human cultural interaction, including the labels we apply to features of the landscape. Of course, like many others I learnt many names from the published Ordnance Survey maps – the One Inch Dublin & Wicklow sheets, the Half Inch Sheet 16 and the Geological Survey maps in B/W One Inch scale. As I rambled over the hills in the later 1970s and early 80s, I became aware of other ‘unmapped’ names through the writings of JB Malone and Liam Price. When I came to produce maps of Wicklow, I decided that I’d look up some of these ‘unmapped’ names and see about recording them. Thus I entered the labyrinth world of placenames! Ten years on, I find that I have conducted a great deal of research into this area. However it could be a full time job in itself, if approached thoroughly in the manner that it deserves. I’ve done what I can to improve the record, within the resources of other survey work and requirement to earn a living etc.

I haven’t published a name on our mapping without careful consideration of the main factors a) what form of the name to choose and b) identifying the feature on the ground and thus on the map. One does not exist properly without the other and one of the weaknesses of many collections of placenames is that often we just have a list of names which whilst interesting, are somewhat lifeless without location. Apart from the study of historical sources, I believe that many useful conclusions can be drawn both by consulting local people who have lived and worked in these areas and examining the landscape on the ground. All sorts of little aspects not readily apparent in a paper listing can then make sense. When I talk to local hill farmers & fishermen I concentrate on a number of aspects: firstly their pronunciation of the name and how it compares to other informants, secondly where the feature is and it’s extent, thirdly what it is and lastly if they know what the name means. This is time consuming but rewarding work, I have met many people who have been both welcoming and helpful in terms of passing on what they know of their local placenames and for this I thank them. Please note that we do not receive any public funding for this type of research and it is done purely out of an interest in these matters and a commitment to improve the record.

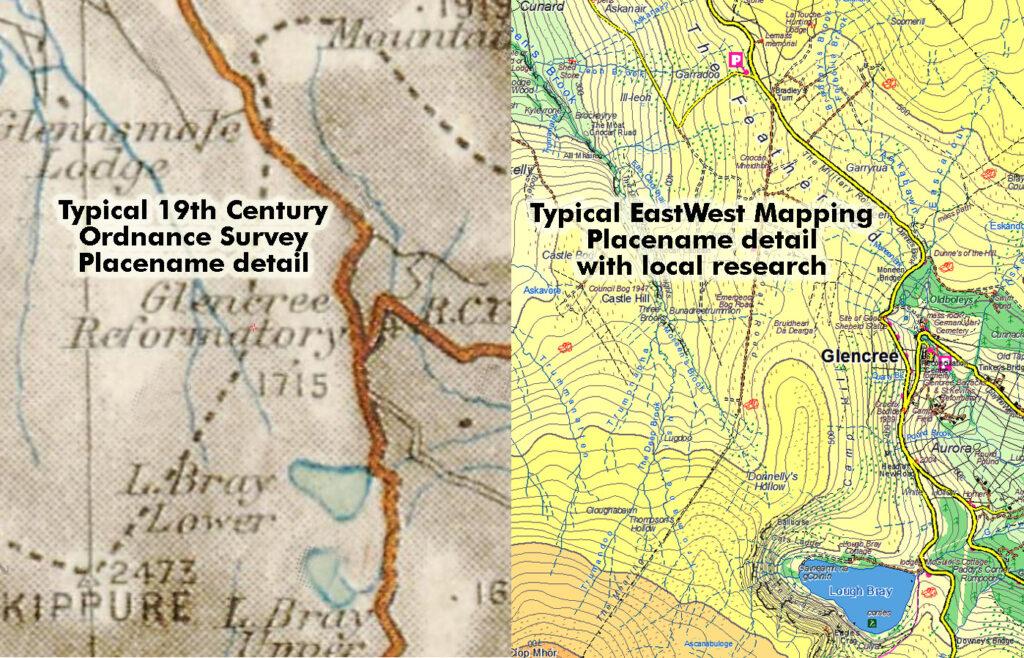

You may ask what is wrong with the placenames we find on the published maps of the Ordnance Survey? The answer to this is, nothing per se, except that their work in collecting these names was largely confined to a decade from approx 1835-45. These were garnered from existing records and collected for the purposes of a map series produced primarily for land valuation. The speed of this survey and the fact that uplands were then, as now considered unprofitable lands, means that very few placenames were recorded in upland areas. Even in the profitable lowlands, the vast bulk of minor placenames were ignored and left unrecorded. The reason was simple, the task was vast and the numbers employed on this work were tiny in comparison to the thousands devoted to land measurement. Successive governments, including those since the foundation of the Free State have done practically nothing to improve this important cultural record. The end result of this neglect is manifest when talking to people who live and work in rural Ireland. The placenames they know often differ from the ‘official’ map versions and additionally they often have an extensive but dying collection of names for a whole variety of features in their districts.

We have researched and published maps both in Leinster and Connacht and it is worth noting that there are significant differences in the origins of placenames between these regions and in our treatment of same.

Placename treatment on our Leinster maps

The eastern side of Ireland has seen and absorbed many waves of cultural influence which have contributed to placenames: Old Irish names and terms, Norse names, Norman & Old English, New Irish, Plantation names, New English and so on. Whilst many placenames have an Irish origin in Leinster, Irish as a spoken language declined steadily in recent centuries, resulting in greater corruption and modification. Our general policy as regards recording placenames in Leinster is:

– use forms that reflect local usage and pronunciation.

– names of English origin are shown in English.

– names of Irish and other origins are anglicised, using standard conventions, but paying close attention to local pronunciation.

– where local informants specifically give placenames ‘as Gaeilge’ and advise that this is how they are known & used locally, then we record them ‘as Gaeilge’.

Placename treatment on our Connacht maps

The west of Ireland presents different challenges – on the one hand, the linguistic structure is simpler. The majority of placenames have an Irish root but there are a good sprinkling of English names deriving from the various landed estates and so on. The Gaeltacht areas where Irish is still spoken are limited in size and shrinking in numbers. However in adjacent districts, many placenames – particularly local names which have been passed on aurally are often very close to spoken Irish, even when the local people do not speak Irish themselves as an everyday language.

How to represent these names on a map is a challenge. We must also look to our customers who will purchase our map product and thereby provide an income to facilitate further work in this area. The majority of our customers do not speak Irish as a first language and would be unfamiliar with a map with placenames recorded primarily ‘as Gaeilge’. We have a need to produce mapping that is accessible to our customers. Most Irish people do not perceive any relevance for the Irish language in their everyday lives. The one area where Irish does touch many people on an everyday basis are the placenames we inherit from our forebears. The presentation of placenames in Irish then is useful in order to foster a basic interest in the language and to encourage further study. Our general policy as regards recording placenames in Connacht is:

– use forms that reflect local usage and pronunciation.

– where Irish forms are given and the correct form can readily be established from pronunciation and/or a description of the feature, then we record the placename ‘as Gaeilge’. e.g. if an informant advises that a particular clear running stream is called the ‘Fiddaungall’, then we represent this as ‘Fiodán Geal’.

– where Irish forms are given and the correct form or meaning is obscure or ambiguous, then we anglicise the name using standard conventions, but paying close attention to local pronunciation. This leaves some room for doubt and is preferable to assigning a definitive Irish version which may be in error.

– English names are recorded in English e.g. if a place is known locally as ‘Hobart’s Bridge’, then it goes on the map as thus, not ‘Droichead Hobart’. The exception to this lies in two instances: firstly where the English name is known and used locally in an Irish version and secondly where an alternative Irish name is known for the same place e.g. Áth Clár – the ford of the plank and probably predating the bridge.

– Major placenames are recorded in anglicised Irish with alternative Irish forms where known. Settlements, townlands, larger rivers and lakes, main mountains and valleys etc. The purpose of this is to make the map more accessible to non Irish speakers.

– Grammar – in bridging the gap between anglicised forms of name as given in local pronunciation and the correct Irish form, we try and follow local use. e.g. if a hill farmer says there’s good grazing up in a small valley locally called ‘Coiredoo’, we write that on the map as ‘Coire Dhú’, rather than ‘An Choire Dhubh’, which would be the standard literary convention. This type of redaction preserves local usage whilst representing the name in an Irish form and is a compromise for non Gaeltacht areas as described above. This approach makes the map more accessible and has the cartographic benefit of obscuring less underlying topographic detail.

The above are guidelines as to our general approach – a quick review of current mapping projects shows that we have broken all these rules in various places but the general approach holds true. It would be impossible to reconcile all the considerations above and we can only trust our own cartographic judgment to present a map that bridges the gap between local usage, our customers sensibilities and the rigors of language.

Finally, we keep a record of the placenames recorded on our maps and their sources, informants etc. This is to assist queries in time to come as to where and from whom, placenames were obtained and notes of a local nature.

Bibliography and web links:

‘The Origin and History of Irish names of Places’ by P.W.Joyce. Three volumes.

‘The Placenames of Co.Wicklow’ by Liam Price. Seven volumes by barony.

‘The Liam Price Notebooks’ edited by Chris Corlett and Mairéad Weaver. Two volumes.

‘Beneath the Poulaphuca Reservoir’ edited by Chris Corlett.

‘The Open Road’ and ‘Walking in Wicklow’ by J.B.Malone.

‘Neighbourhood of Dublin’ by Weston St.John Joyce.

Journals of the Roundwood & District Historical Society.

The National Library of Ireland in Kildare Street, Dublin has a collection of old maps. Many of these are available for public viewing but you must apply for a readers ticket etc.

‘Legends of Mount Leinster’, ‘Evenings in the Duffrey’ & ‘The Banks of the Boro’ by Patrick Kennedy.

‘Carlow Granite’ by Michael Conry.

‘Rathnure & Killane: a Local History 1798-1998’ edited by Gloria Binions

‘The O’Leary Footprint’ edited by Philip Murphy & David Hughes

‘Graiguenamanagh A Varied Heritage’ & ‘Graiguenamanagh A Town And It’s People’ by John Joyce.

‘Scottish Hill Names’ by Peter Drummond

‘Logainmneacha Mhaigh Eo’ by Fiachra MacGabhann

‘Clare Island Survey’ by Royal Irish Academy

‘Logainmneacha Baile Chruaich’ by Uinsíonn Mac Graith agus Treasa Ní Ghearraigh

‘Medieval Ireland – Territorial, Political and Economic Divisions’ by Paul MacCotter

‘Stones of Aran’ & ‘Connemara’ by Tim Robinson

The Field Names of County Meath

The Field Names of County Louth

www.logainm.ie – website of the Placenames Commission, a good starting point with old records (check sources)

www.teanglann.ie – Ó’Dónaill Irish dictionary

www.dil.ie – a dictionary for old Irish

www.osi.ie – Ordnance Survey Ireland, look up old Six Inch and 1:2500 scale maps

downsurvey.tcd.ie – William Petty’s Down Survey, view 17th century maps of Ireland

www.placenamesni.org – placenames in Northern Ireland

www.cnag.org – Scottish mountain names

www.placenames.ie – Cork & Kerry placenames

www.meathfieldnames.com – Meath field names